How policy really works

Traditional approaches to policy impact run into problems when we take a simplistic or overly instrumental approach to either policy or impact. In spite of the best intentions and hardest work, many attempts to use research in policy settings have limited success. For example, the research that underpinned “green revolution” policies to mechanise and industrialise agriculture to provide food security across Africa in the 1970s were based on sound research that had previously only been applied in the global North. More recent approaches to tackle food insecurity via genetically modified (GM) crops have run into similar problems, despite the fact that they were based on rigorous research. In their new setting, tractors broke down and parts were not available to fix them. GM crops were more productive but had to be used with specific (and expensive) herbicides and pesticides, and harvested seeds were not fertile so farmers couldn’t collect seeds for next year’s crop, having to buy new seed each year.

There can be significant time-lags between research funding applications to the publication of findings (typically 3-5 years). Given that few current governments will still be in place five years from now, this is a problem. Most policy colleagues are looking for answers to questions within hours or days (it is rare that they can wait weeks). Even one year is too long for most policy teams to wait for an answer. This means that to help policy colleagues, most of us will need to rely on existing literature and expertise to meet current needs. While we are doing this, we have opportunities to building trusting relationships with individual policy colleagues, and our reputation with wider policy teams (given that most individuals will move to new positions over the course of a research project). This will then position us to identify relevant windows of opportunity when our research is eventually ready.

If our task is to get our research to the people who can make decisions, then simply publishing your research open access is not enough. There is a difference between your research being available in this way, and it actually reaching those who could most benefit from engaging with it. There is also a difference between your research being available and understandable; the majority of open access papers are unintelligible to anyone outside the discipline in which they were published. Module 3 will consider a range of ways to make your research more understandable to different policy audiences.

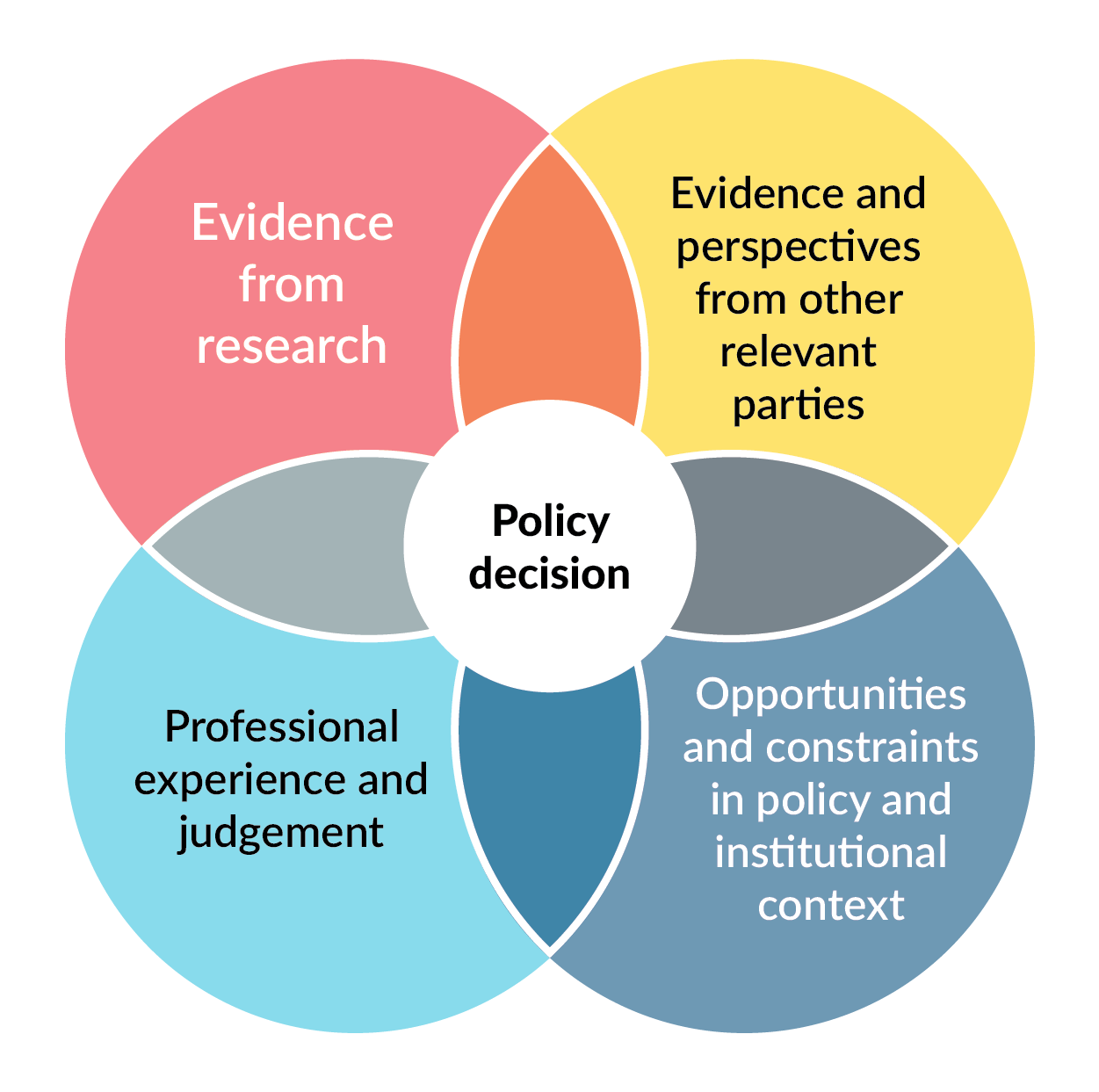

Once your evidence has reached someone who might be able to use it, and they have understood your findings, it will be just one of many inputs to any policy decision. Not all research is useful as evidence, and not all evidence is research-based. In addition to other researchers and findings, there will be other arguments vying for the attention of the policy colleagues who are interrogating your research. These may include moral and ideological arguments, that in the view of the policy professional may demand a course of action that directly contradicts your evidence. Unconventional though this may sound, there is an argument for identifying and representing these perspectives yourself, and presenting them alongside your research evidence. These concerns may arise from the very people you hope that the policy will benefit, and so it is possible to argue that by representing these voices, we have the potential to democratise policymaking. For example, Box 1 describes how researchers from the University of Leeds used social science to give voice to marginalised children, enabling their perspectives to be heard and help shape policy.

Amplifying the voices of children in poverty

Dr Gill Main’s research aimed to put the experiences of children and families living in poverty at the heart of the UK poverty debate and help reach the ultimate goal of ending poverty for all. Dr Main surveyed families and partnered with schools, a local authority and charities to bridge the gap between academic research and society. This research collated and amplified the knowledge of families with first-hand experience of living in poverty, reducing feelings of stigma or shame associated with their experiences. Main has changed the policy rhetoric to better represent the real-world experiences of those living in poverty.

Families with first-hand experience of living in poverty felt heard and gained confidence and self-esteem; many found a new way of understanding poverty as a social injustice and not as their personal failing. Main’s research also changed how policies are designed in the city of Leeds to address poverty, ensuring the voices of children and families living in poverty are listened to. This research has helped local authorities, charities and advocates to develop a better understanding of poverty issues, and to design interventions to help work towards a fairer society for everyone.

Finally, in addition to inputs from research, others with a legitimate claim to comment on the policy and their own professional judgement, your policy colleagues will be constrained by the environment in which they are working. For example, there may be both opportunities and constraints arising from the political and institutional context in which they find themselves. Ideologies, norms or previous policies may influence how a problem is perceived and framed, and constrain the range of options deemed politically feasible. Equally, the political context may present windows of opportunity as a result of elections or the political imperative to respond to a crisis or some other focussing event. The factors influencing policy decisions are summarised in the figure below:

Most policy impact guides and toolkits present an attractively simple, but I will argue simplistic, model of how to influence policy:

- Work with policy colleagues to clearly identify a policy problem you can help with;

- Conduct research or draw on existing work to identify technically and politically feasible solutions to the problem;

- Use objective criteria and political goals to compare and rank solutions;

- Conduct research or draw on existing work to predict the likely outcomes of the top-ranked solutions; and

- Make concise evidence-based recommendations to solve the problem, sharing the pros and cons of each solution and using visual aids to communicate clearly and make the problem seem solvable.

What could possibly be wrong with such a tried-and-tested approach to working with policy? If politics were simple, then such a simple approach might work, but the problem is that reality is a lot more complex:

- What if policy colleagues in different departments (or even in different teams within the same department) see the problem in very different ways.

- What if each of those ways of seeing the problem are a result of assumptions based on previous policies (for example posit economic growth as an imperative) and fail to see the problem from the perspective of those who are being negatively impacted by current policies?

- How is the definition of what’s politically feasible shaped by the way a government has consistently stereotyped and overlooked the needs of certain populations?

- What if, by only considering options that are politically feasible for the current administration, you might further marginalise the most needy in society?

- Who represents their interests, and do we have a responsibility to share our power as researchers to give voice to those who are rarely heard in the corridors of power?

- Who chooses the supposedly objective criteria for evaluating policy options, and how do these criteria reflect their values and assumptions, leading to biases in decision-making that protect the interests of others with similar values and assumptions?

- Can we ever predict with any accuracy how a policy might play out in a complex system that we do not fully understand?

- What if our policy colleagues don’t actually have the power we think they do to either develop or implement policy?

- What if power is decentralised to regional governments and delivery agencies who we aren’t talking to, and implementation depends on the unpredictable decisions of countless people as they interact with unknown future events and other drivers of change?